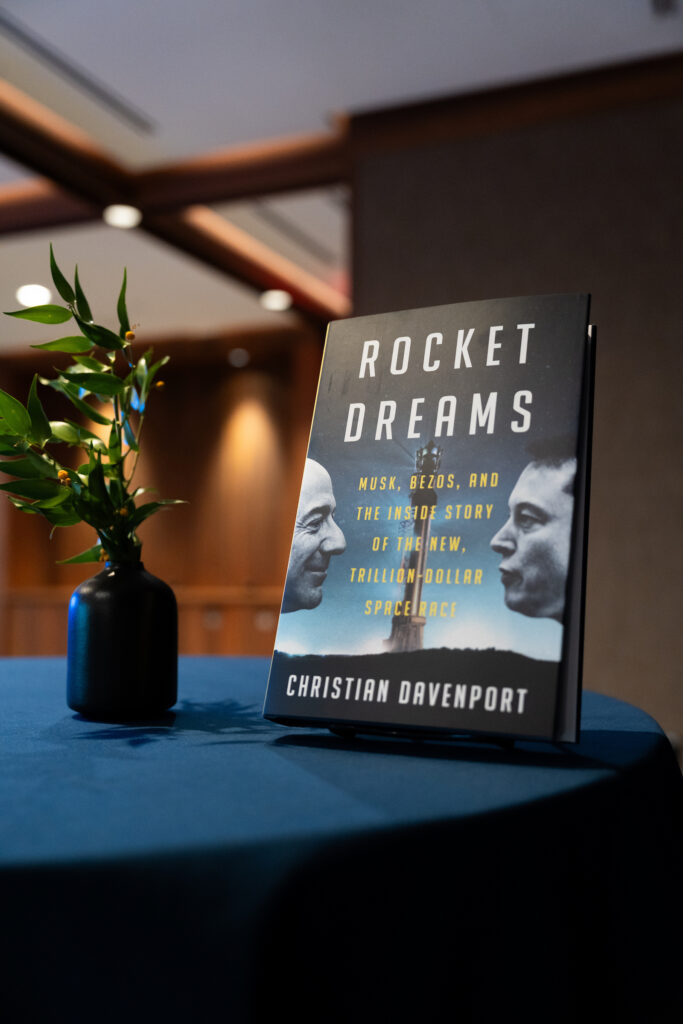

The state of space: 4 takeaways from Christian Davenport’s ‘Rocket Dreams’ book launch

Key insights from the Washington Post reporter’s conversation with former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine on the commercial space industry and the nation’s new space priorities.

The New Space Age looks much different than the space race of the 20th century, yet it’s still marked by fierce competition. In his new book, Rocket Dreams, Christian Davenport, space industry reporter for The Washington Post, provides an inside look at the rivalry between billionaires Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk as Blue Origin and SpaceX compete to build commercial rockets. He also addresses the new space race between the U.S. and China to return humans to the moon and, eventually, Mars.

At his book launch, part of the Authors & Insights series at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center, Davenport spoke with former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine about defining moments in the story of how the U.S. has come to embrace the commercial space industry to support its new space ambitions and help shape humanity’s off-planet future.

These are four broad takeaways about the future of space from their conversation.

- The government still directs space priorities, even for private space companies

While SpaceX has primarily focused on getting to Mars, Davenport noted that the company has also had to compete for government contracts to fund these missions, which has affected where it has put its energy.

Davenport pointed to 2017 when Musk said at a space conference that the U.S. should have a moon base already, garnering a lot of attention as a break from his fixation on the Red Planet.

“What that indicates is when an administration makes a decision that says, ‘Hey, Space Policy Directive 1 is to go to the moon,’ it fundamentally changes the direction that the whole country moves, including the contractors who created their companies for entirely different reasons,” Bridenstine added. “Everybody pivots because they’re chasing those dollars.”

- The commercial space industry must have healthy competition, not just one dominant player

Davenport noted that for a long time, Boeing was NASA’s primary commercial space partner. In his book, he describes a shift early on in NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, when Phil McAlister, the former director of commercial spaceflight development at NASA, pushed for more than one commercial provider, paving the way for SpaceX to become a more central NASA collaborator.

This underscored the notion that “you cannot just rely on one company, on one person, [and] that having competition, multiple providers, more people out there, is ultimately good for the whole space enterprise,” Davenport said.

Bridenstine echoed this, saying that as NASA administrator, he often said a commercial space industry can’t exist if there aren’t multiple providers competing on cost and innovation. Additionally, each of those providers must have customers that aren’t NASA or the government.

“In the end, the goal is to say, ‘If the government quits paying, does it continue?’” Bridenstine said. “If the answer is yes, then in fact it is a commercial system.”

- The future of space is intertwined with national security

Davenport specifically mentioned satellite security as an issue he’s been following over the past several months, especially since we rely on satellites for everything from Uber to bank transactions. He noted that there’s even a website for tracking where GPS satellite services are being disrupted or interfered with. “The ramifications of that are scary,” he said.

- Two space races are happening simultaneously

Bridenstine made the distinction between two competitions underway: one to commercialize space, a potential “multitrillion-dollar market,” and a “lunar land rush”—as Davenport calls it—to beat China to the moon. Sometimes they’re at odds with each other.

“I think it’s important to turn to commercial industry to deliver on behalf of the American taxpayer when we can have commercial markets do that,” Bridenstine said. “But when you hear the U.S. government say we’re going to beat China to the moon … and instead, there are contractors that are interested in disrupting a paradigm, it’s going to take a lot longer.”

This disconnect stems from the fact that the geopolitical race focuses on achieving a specific goal quickly, while the commercial one focuses on how that goal is achieved.

“If we’re trying to beat China to the moon, then we need to have programs to beat China to the moon,” he said. “If we’re trying to fundamentally disrupt and transform how we get to the moon, that’s a different thing. Maybe we’ve got to figure out, what is our primary objective here?”