As the National Flood Insurance Program is pushed to its limits, how should we address flooding?

With the NFIP set to expire at the end of September, three Hopkins experts weigh in on why flood mitigation—not just flood response—is key to addressing the growing frequency of flooding

In 2024, the National Flood Insurance Program paid out $8 billion in claims, as Florida, North Carolina, and other states rebuilt from a devastating hurricane season.

The program—the nation’s largest single-line insurance program—covers 4.7 million policyholders nationwide, providing nearly $1.3 trillion in coverage against floods.

But the NFIP is set to expire at the end of September, unless Congress votes to reauthorize it. Here, three Johns Hopkins experts provide research-backed insights on reforming the NFIP, as well as developing a more holistic approach to flood mitigation.

NFIP limitations

The NFIP was founded in 1968 to fill the gap left by private insurers uninterested in entering the flood market because the risk is too high and too concentrated. Recent estimates say over 95% of residential flood policies are bought through the NFIP, though that percentage could shrink as the private market grows.

Because of how expensive floods are to respond to, flood insurance is “increasingly unattractive” for private insurers to offer, explained Seydina Fall, a professor at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School whose work explores how infrastructure projects can help communities be more resilient to climate-related challenges. It’s not just water damage that drives the price up, but the scale of the destruction, too.

Flooding, like wildfires, affects many homes at the same time, causing “catastrophic losses” for insurers. That makes it hard for them to manage risk across a portfolio because the risk hits all at once. For example, in 2011, Tropical Storm Irene led to $63 million in insurance claims, $153 million in state and local costs, and a staggering $603 million in federal outlays in Vermont, largely due to flood damage.

While the NFIP has historically been the primary provider of flood insurance to the public, it now faces serious challenges, as home values have increased and flooding has become more common.

“The NFIP is overwhelmed in terms of demand,” Fall said. “There’s a market failure.”

4 solutions for addressing the rise of flood risk in the U.S.

Hopkins experts pointed to a variety of updates to existing policies, as well as preventative measures to mitigate flood damage.

- NFIP reforms

Fall offered two potential policy reforms for the NFIP:

- Increase the policy limits. The NFIP only provides building property coverage up to $250,000, while the median American home sale price is $422,400. It’s a discrepancy that leaves many policyholders without coverage for their entire home.

- Restructure the debt load. The program also has more than $20 billion worth of debt. Since 2005, losses have exceeded premiums by $36 billion, a number that will likely grow without reform. Fall suggested the NFIP should buy back its debt to give it more spending flexibility.

“There are some legal complications and moral hazard-type issues in canceling the debt,” Fall said. “Buying it back would clear some of those hurdles as long as the price for the buyback is seen as being competitive in an ‘arm’s-length’ transaction.”

Moral hazard, or engaging in riskier behavior because there’s guaranteed insurance coverage, is a behavior Gonzalo Pita, an associate research scientist at the Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering who models natural disaster risk, also flagged. The federal government, he said, should monitor and reduce the risk of moral hazard as well as adverse selection, or the tendency for people with high risk to buy insurance and those with low risk to skip it.

Both skew insurance risk pools towards homeowners likely to need a payout, causing the NFIP to pay inflated claims and become unsustainable. Minimizing these two behaviors would help the program manage the debt better, Pita said.

At the same time, he added, continuing to analyze and optimize risk layering strategies, an approach that brings together multiple risk management tools, can help prevent the government from bearing the full load of flood damage costs as the insurer of last resort, which increases the public debt.

- Reassess FEMA flood maps

The FEMA’s Flood Insurance Rate Maps do more than their name implies. In addition to setting the cost of federal flood insurance, the maps also determine which properties require insurance and help potential homeowners determine the risk of floods in a given area.

But according to Natalie Exum, environmental health scientist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the flood maps are out of date and no longer accurately reflect risks.

“When we say the 1-in-100-year storm or the 1-in-1,000-year storm, it’s based on very old projections of rainfall,” she explained. “There’s a lot of spatial technology now that could improve those estimates.”

- Proactive risk mitigation

Beyond those reforms, Fall said it’s time to think about flood insurance differently to keep the NFIP solvent.

“What we really need to focus on is to try to find innovative ways to be able to manage and mitigate those risks,” he said.

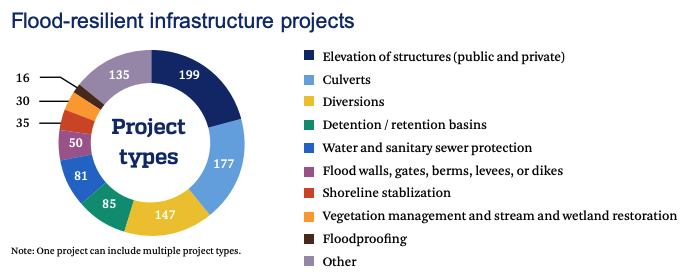

Addressing upstream risks could prevent flood damage in the long run. In fact, an analysis from the Congressional Budget Office found that every $1 spent on flood protection projects prevents $2-3 in damage.

Possible interventions, Fall said, include implementing nature-based solutions, such as wetland restoration, and using more flood-resistant materials, such as concrete and brick, when building new facilities.

Source: The Local Economic Impact of Flood-Resilient Infrastructure Projects by Matthew E. Kahn, Mac McComas, and Vrshank Ravi Johns (Johns Hopkins University’s 21st Century Cities Initiative)

Pita echoed some of Fall’s points, and recommended more investment in certain infrastructure projects that can save money in the long run, such as dams and levees.

“It’s not just one silver bullet; it’s a menu of interventions,” he explained.

- Local policy levers

One critical aspect of that menu is zoning laws, which communities can use to restrict building to certain regions. One 2019 assessment found that zoning policies could generate between $1.03 and $2.20 of benefits per dollar of costs generated if areas with a flooding probability of up to 1% are zoned.

Cities such as Norfolk, Virginia; Charleston, South Carolina; and Stonington, Connecticut have all used their zoning codes to direct development away from flood-prone areas and incentivize more density outside of areas likely to flood.

For communities considering zoning reform, Pita developed a method through which they can build a custom model that estimates expected damage caused by rivers overflowing their banks. This can help address outdated and inaccurate flood maps that make it difficult for communities to prevent building in flood plains. Better risk modeling efforts also help manage potential liabilities, which helps the government design a better disaster risk financial strategy, Pita said.

“It’s not just one silver bullet; it’s a menu of interventions.”

– Gonzalo Pita, associate research scientist at the Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering

His method not only provides users with step-by-step instructions but also measures and assigns numerical values to the level of uncertainty in individual flood damage forecasts, giving governments a clearer picture of how reliable their predictions are. The approach is both more accurate and more affordable than other options, and could be used by city planners, risk modelers, insurance regulators, and FEMA mapmakers.

“These types of insights could inform policy directly and indirectly, from enabling smarter zoning laws and budgeting for asset maintenance to designing disaster insurance programs,” Pita said in a 2023 interview. “All of this is to say that better flood damage data and predictions have the potential to have far-reaching benefits.”

Why mitigating flood damage is increasingly important

Experts emphasized the need for proactive solutions as climate change contributes to more frequent and severe storms and floods become more common and more costly. The consequences extend beyond physical damage, straining local economies, federal resources, and community health.

Damage to local infrastructure and economies

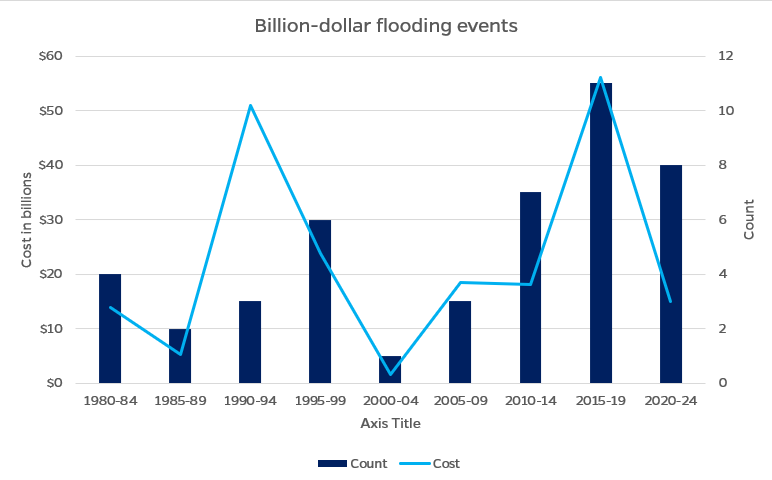

Floods cost the nation between $179.8 and $496 billion each year—the equivalent of 1-2% of U.S. GDP in 2023—according to a 2024 assessment from the Democratic staff on the Joint Economic Committee. More than half of the economic cost comes from the commercial impacts of flooding, whether from direct lost output or indirect loss from downtime days.

Data source: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information

Strain on federal relief resources

The cost of natural disasters each year often exceeds the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s resources. A Congressional Research Services report found that FEMA’s Domestic Relief Fund, the primary source of funding for the federal government’s domestic general disaster relief programs, did not have enough money to cover its obligations four out of five fiscal years between 2020 and 2025.

Congress typically allocates additional funds for the agency as needed, but the persistent shortfalls highlight the additional strain that extreme weather events put on disaster relief funds.

-

45

Number of flooding events from 1980-2024 where estimated damages exceeded $1 billion, with total losses at $146.5 billion

Risks to community health

The impacts of floods extend beyond infrastructure damage; contamination from flood water can harm Americans’ health. When heavy rainfall overwhelms sewers and drainage systems, human and animal waste can flow into drinking water, making people sick after they consume it.

Exum, who has researched the impacts of heavy precipitation and flooding on the safety of drinking water and outlined ways leaders can better protect community health, said sudden gastrointestinal illness after floods is common, as people don’t think to test their drinking water after a storm. While many people recover at home without complications, some end up in the hospital.

Exum offered two main recommendations for policymakers concerned with how flooding affects drinking water:

- Consider how to transport clean water into a community following a storm. She pointed to the issues North Carolina faced with trucking in drinking water after Hurricane Helene destroyed the state’s infrastructure.

- After a storm, states and localities should have protocols in place to alert residents about any water quality risks.

Exum noted that these steps will become increasingly important in the coming years as climate change makes flooding more common.

“The hotter the air,” she said, “the more water that’s going to be in the atmosphere, and so the more rain that’s going to fall.”