How a new Hopkins drug supply chain dashboard can help tackle U.S. drug shortages

The Johns Hopkins Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Dashboard is the first of its kind to track drug production, shortage history, and shortage risk factors. Here’s how policymakers can use the data to help strengthen drug supply chain resilience.

Just weeks ago, the drug leucovorin made headlines as the FDA moved to approve the medicine for potential autism treatment. Yet missing from the coverage was the fact that the U.S. has had a shortage of leucovorin, which is typically used for cancer treatment, for 13 years.

This is indicative of broader supply chain issues driving drug shortages in the U.S.—a challenge that has attracted the attention of lawmakers from both parties, who are now advocating for a more resilient pharmaceutical supply chain. Yet any attempts to find effective solutions to strengthen the nation’s pharmaceutical supply have faced one main roadblock. Today, health care providers, hospitals, and patients can only see one part of the supply chain: the drug price.

“There is an information gap that permeates all of the attempts to resolve this problem,” said Mariana Socal, associate professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management.

To address this lack of visibility, she led a team of Johns Hopkins experts to build the Johns Hopkins Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Dashboard, which launched in June 2025. Funded by a Johns Hopkins Nexus Award and later by a grant from the U.S. Department of Defense, the team has worked together for over a year to identify the right supply chain data sources, then link those sources together to tell a complete story about all the drugs available in the U.S. market. This data, the team said, can help address the key vulnerabilities that threaten the security of the U.S. drug supply chain.

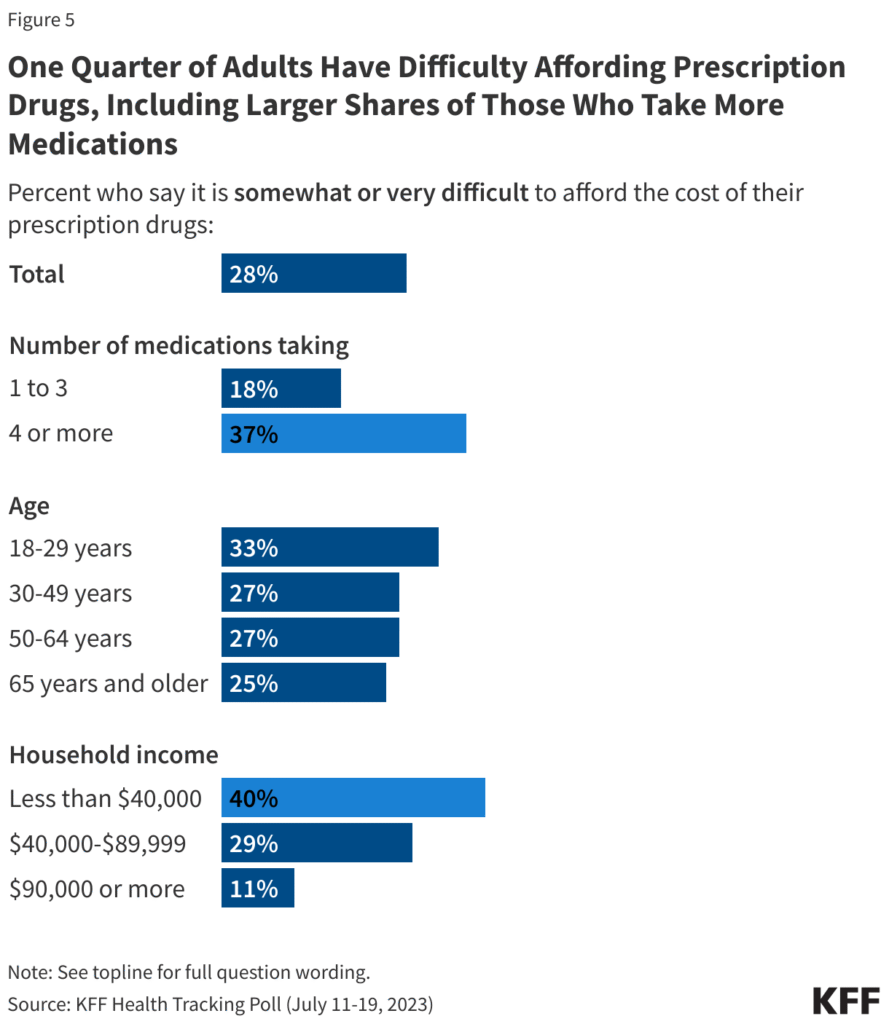

At the core of concerns are the weaknesses of a global production network, which has historically helped diversify the sources of drugs to the U.S. market and keep prices down, especially for generic drugs. Still, about 1 in 4 Americans cannot afford the drugs they need, and cheaper generic drugs, which account for 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., are often out of stock. Experts say the growing overreliance on foreign sources for drugs is leaving the U.S. increasingly vulnerable to supply chain disruptions—a reality that was particularly apparent in 2020.

“The COVID-19 pandemic was really a wake-up call,” said Tinglong Dai, professor at the Carey Business School, as it highlighted a pharmaceutical supply chain that “can break any time.”

-

14%

Percentage of active pharmaceutical ingredients—raw materials required for the U.S. generic drug market—that are manufactured domestically.

This fragility didn’t develop overnight. Rather, the pandemic exacerbated weaknesses that had long existed in the supply chain.

“It helped reveal the multiple vulnerabilities in pharmaceutical production, distribution, regulation, and oversight that were not necessarily recognized as policy priorities until then,” Socal added.

Global health emergencies are just one potential disruption that can put the American drug supply at risk. Geopolitical tensions stemming from armed conflicts and trade wars, for example, also threaten the pharmaceutical supply chain, as do natural disasters that impact domestic supply.

“We live in a very different world than before,” Dai said. “The global supply chain that we built for the past 30 years is unraveling, and we can no longer afford to take it for granted.”

To build resilience, leaders must first have the information they need to identify gaps. Using statistical models, data analytics and visualization, and large language models, Hopkins experts have identified and linked supply chain information for over 60,000 drugs in the dashboard. Next, they plan to create digests of this information to display each drug’s level of vulnerability, including its shortage risk.

“At the end of the day, it is all about identifying, measuring, and sharing information on the risk and vulnerabilities associated with each drug and manufacturer, empowering consumers and providers, and informing policymakers who aim to find a solution for our pharmaceutical supply chain problems,” Socal said.

Cost of drug shortages

Supply chain disruptions, whether a widespread shortage or simply a low supply of a drug, impact purchasers, prescribers, and consumers.

“Everybody has to adapt to that disruption, and the adaptation process costs money and resources to everyone involved,” Socal said, including the procurement of a potentially more expensive substitution drug. This, in turn, could force patients to buy a pricier medication.

Drug quality issues

Shortages can also impact the quality of treatment. Substitutions are often less effective and less safe than the main brand or manufacturer of that drug, Socal said. By increasing supply chain transparency, the dashboard provides a pathway to address and prevent these issues, building a more sustainable drug supply for the sake of national security and public health while ensuring affordability.

What does the Hopkins Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Dashboard show?

The interactive dashboard allows the American public, including patients, health care providers, and policymakers, to identify where a drug comes from. It aggregates publicly accessible data on multiple parts of the supply chain into one cohesive, easy-to-understand tool. Users can search drugs by brand name or substance name and see:

Historical shortage information: Whether the drug has experienced a shortage in the past five to six years and how long that shortage lasted.

Manufacturer information: Which countries manufacture the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and the finished dosage form (FDF) of the drug, and who the manufacturers are.

Regulatory action: The results of FDA inspections on finished drug manufacturers and any regulatory enforcement actions, such as citations and recalls.

Hopkins updates the dashboard data every three months.

“The global supply chain that we built for the past 30 years is unraveling, and we can no longer afford to take it for granted.”

– Tinglong Dai, professor at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School

How can policymakers, agencies, and institutions use the dashboard to address drug supply chain vulnerabilities?

The dashboard can help leaders make informed policy decisions to mitigate drug shortages in the short term and develop resilience strategies for the long term.

Identifying drugs of national interest. Federal agencies could use the dashboard to identify drugs they should safeguard, whether for military deployment, medical countermeasures in the event of a conflict, or public health.

It could then use this information to establish supply-side incentives to diversify the sources of these drugs, similar to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ recent policy to pay certain hospitals that establish and maintain a six-month buffer stock of essential medicines.

Similarly, state government initiatives, such as the state of California’s CalRx, could use the dashboard to determine target drugs to develop.

Anticipating inspection-triggered shortages. If an FDA inspection of a major drug manufacturing facility requires corrective action or results in a recall, it can disrupt production and trigger a shortage. These inspection results, documented in the dashboard, could help agencies see if a specific manufacturer or product type has persistent quality assurance issues. They could then take proactive measures before production disruptions impact patients.

Spotting over-dependencies. Some generic drugs can appear to have a resilient supply chain with multiple manufacturers, but many tend to be re-labelers who ultimately get their APIs from only a few sources, dashboard experts said.

“Our research has found that 1 in 4 generic markets has an undetected vulnerability in the pharmaceutical supply chain,” Socal said. This means four or more manufacturers are producing a finished drug, but only three or fewer manufacturers are producing the necessary active ingredients for it.

By providing insight into the production of both the APIs and the FDFs, the dashboard can help policymakers identify which manufacturers or countries dominate the production of essential drugs. In many cases, drugs with a heavy foreign dependency rely on only one or two production facilities, Dai said.

Making strategic procurement decisions. As a more immediate solution, the data can help medical institutions with day-to-day procurement decisions. They can use the dashboard to better prepare for critical drug shortages and identify alternative drug manufacturers to lean on.

Determining onshoring opportunities. The dashboard can also play a role in developing broader strategies for strengthening the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain by helping leaders decide which drugs it should expand domestic production of.

“What if we buy more from Italy? What if we build a factory here in California? What if we build a factory here in Maryland?” Dai said. “We can’t move forward in our discourse, let alone take action, unless we share a trusted view of the supply chain behind our prescription drugs. That’s exactly what we aim to develop through the Drug Supply Chain Dashboard. When people have easy access to, and take active advantage of, this uniform source of information, we will finally be able to meaningfully engage with each other in terms of understanding the consequences of interrogating answers to these what-if questions.”