Cross-state telehealth laws restrict access to essential care. Hopkins researcher says these reforms would close the gap.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the benefit of easing cross-state telehealth licensure rules. Is it time for the U.S. to make cross-state telemedicine permanent?

Key takeaways

- State-based physician licensure regulations are a major barrier to modernizing patient care through cross-state telehealth, as they require doctors to be licensed in the state where a patient is located to virtually meet with them.

- The COVID-19 pandemic provided a temporary snapshot of how easing these restrictions expands access to essential care while reducing provider burden.

- A Johns Hopkins researcher has collaborated with dozens of experts to identify two policy approaches they say will help modernize telehealth while maintaining patient safeguards: a continuity of care model and a national telehealth registry.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, as people stayed in their homes, health care left the confines of the doctor’s office.

For nearly two years, telehealth soared in popularity, providing patients with a level of access to health care professionals that had never existed before. You could schedule a live video call with a doctor, no matter where you or they were located in the U.S. The state-specific licensure rules that had once restricted cross-state telehealth quickly melted away as states passed pandemic-related waivers allowing telemedicine beyond their state lines in response to the health crisis.

But as the COVID pandemic faded, so did the flexibility to schedule a virtual visit with doctors in other states. States began to restore their strict licensure requirements, preventing patients from accessing health care services through interstate telehealth, even in very common scenarios.

Doctors must typically be licensed in the state where their patient is located at the time of care. This means that, if you’re traveling to a different state, you usually can’t access telehealth services with your regular doctor, and out-of-state college students must often return home to get care from their established physician.

The current state of cross-state telehealth

Physician licensure regulations, which are controlled by each state, are the main barrier to broader interstate telehealth access. If doctors want to perform telehealth visits with patients in five different states, they need to apply and pay for five different licenses. Each state has its own standards and laws related to telehealth.

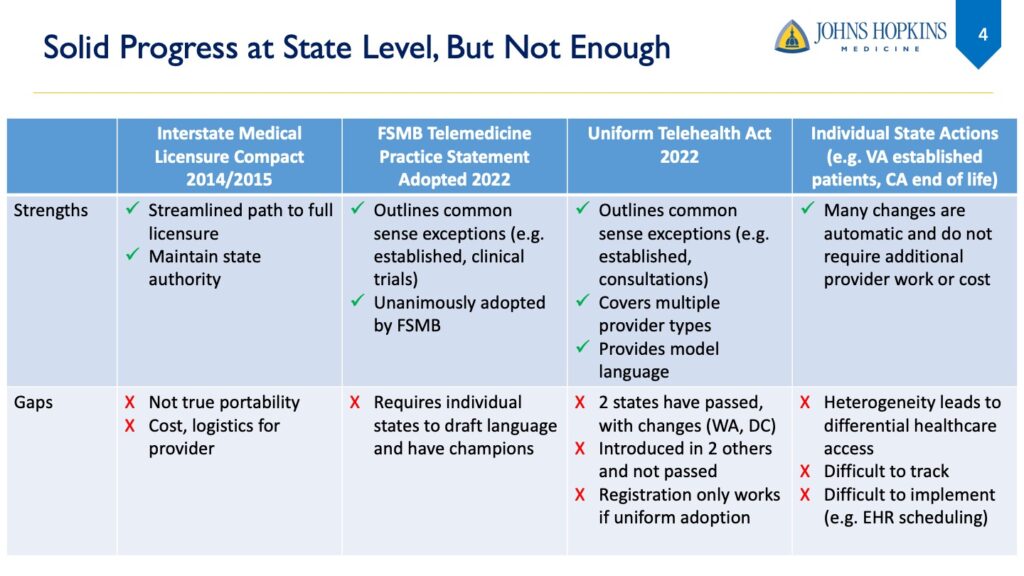

While there has been incremental progress over the past 10 years to promote reform, enacting changes still requires state-by-state adoption. For example, federal grants helped establish the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC) in 2014, which still requires providers to get licenses and pay licensing fees in each state separately, even though the paperwork is streamlined.

Why isn’t the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact a sufficient solution?

Unlike the Psychology Interjurisdictional Compact, also known as PSYPACT, the IMLC doesn’t allow doctors to provide cross-state telehealth without multiple licenses upon registering. Rather than allowing for portability of one state license for use in another state, it streamlines the application process for multiple licenses by allowing states to share paperwork.

Doctors must still pay the IMLC fee, pay additional fees for each state they would like to be licensed in, and submit fingerprints to their primary state of licensure for a criminal background check. The Compact fee is $700, and individual state licenses are usually several hundred dollars each, with some costing upwards of $800.

Hypothetically, if a doctor wanted to provide telehealth to all 40 participating states, the cost of the Compact would be more than $20,000 every 2 years, according to a Cicero Institute telehealth report.

This results in varying state-specific standards that are difficult to track and operationalize, prompting the need for “federally clarifying what should be occurring between states on this issue,” according to Helen Hughes, medical director for Johns Hopkins Medicine’s Office of Telemedicine.

Cross-state telehealth expansion has seen bipartisan federal support in the past. The bi-cameral Temporary Reciprocity to Ensure Access to Treatment (TREAT) Act, introduced in the House by Reps. Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.) and Bob Latta (R-Ohio) and in the Senate by Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) and former Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) in 2020, initially sought to allow health care professionals to provide telehealth care across state lines during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023, it was reintroduced to allow mental health telehealth services across state lines during a declared national emergency.

Today, government officials are further acknowledging the need to modernize the health care experience by building and using more digital tools to deliver service. This demonstrates a growing recognition that expanding technology capabilities in the health care system can improve patient outcomes and ease administrative burdens on doctors.

Challenges of the current telehealth landscape in the U.S.

These licensure restrictions create unnecessary time and cost burdens for patients across the country, Hughes said, with some traveling hours for appointments that don’t actually require the patient to physically be there. People impacted most by cross-state telehealth restrictions include:

- People with rare diseases and cancers

- College students who live out of state for school

- Clinical trial participants who don’t live near academic medical centers

- Patients with palliative care needs

- Transplant recipients

- People who need mental health services

- People who live in rural areas

- People with complex or chronic conditions traveling out of their home state

These groups often face disproportionately high barriers to access because of the limitations of where they live, regulatory red tape, and shortages of local specialists. A 2021 study found that during the pandemic, people in rural communities were more likely to receive out-of-state telemedicine care, and there was high out-of-state telemedicine use for cancer care. While tests, therapies, and surgeries must be done in person, pre- and post-visit care can often be done via telemedicine.

Shannon MacDonald, senior medical director of the Southwest Florida Proton Center and senior consultant for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, treats children with cancer or patients with rare base-of-skull or spinal tumors, more than half of whom she said travel from out of state to see her.

The burden of an initial diagnosis is exacerbated by cross-state telehealth barriers. Patients newly diagnosed with cancer, she said, don’t have the luxury of time, nor the resources to travel in order to determine where to get treatment.

“They’re also overwhelmed with a new diagnosis of cancer for themselves or for their child, and they shouldn’t have to fly across the country to get an opinion when they could spend 30 minutes to an hour getting a video consult,” MacDonald said. “I think it’s quite unfair to put that burden on them.”

Proposed telehealth licensure reforms to expand access to essential care

Hughes, MacDonald, and more than 60 other experts convened at the Hopkins Bloomberg Center earlier this year to identify two strategies they recommend for policymakers as the most impactful and feasible pathways to modernize telehealth while maintaining patient safeguards.

- A continuity of care model

This would include a national clarification, likely through congressional action, stating that established patient care, or continuity of care, is allowed across state lines. Once doctors have established a relationship with a patient, which the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services defines as three years, they can continue to interact with that patient across state lines for a certain period of time, such as no more than three years.

Doctors would need to follow laws both in the state where they established care and in the state where the patient is located at the time of care. This mirrors the way doctors already communicate with patients on the phone or through digital patient portals to ensure continuity of care after seeing them.

2. A national telehealth registry

A proposed collaborative national telehealth registry, operationalized by national groups like the Federation of State Medical Boards and the Department of Health and Human Services, would allow doctors in good standing to establish new cross-state relationships with patients when medically appropriate. Through national registration, doctors could obtain an active, unrestricted licensure in one state that allows them to also provide cross-state care for urgent, high-impact conditions, such as rare and life-threatening diseases. For providers and health systems, this would provide one national, streamlined approach to provide interstate telehealth.

The federal government has allowed some exceptions to state licensure restrictions to meet the needs of specific patient populations in the past, including:

- VETS Act: A Department of Veterans Affairs doctor can see a Veterans Affairs patient in any state if already licensed in one state.

- Military Spouses Licensure Relief Act: A military spouse who is licensed and has moved to a different state due to military obligations can use their original state licensure to practice for a period of time.

- Sports Medicine Licensure Clarity Act: Doctors and other professionals who travel with sports teams can use their licensure to practice while traveling with a team.

In fact, when VA implemented its Anywhere to Anywhere program in 2018 allowing VA health care teams to provide cross-state telehealth, it saw an 17% increase of VA telehealth services over the prior fiscal year.

“To me, there’s this coalescence of things that say this is an issue that can be solved, should be solved, and maybe now is the right time to solve it,” Hughes said.

-

1/20

Medicare patients who used telemedicine services from January-June 2021 contacted an out-of-state clinician. Source

-

2-4x

How much more likely rural patients are to travel across state lines for cancer care compared to urban patients. Source

-

500K

Number of college students who lose access to psychiatric treatment each year because of licensure barriers to telehealth mental health care. Source

Benefits of cross-state telehealth reform

The COVID-19 pandemic shed light on the potential advantages of more flexible licensure rules for interstate telehealth. Experts and research say permanent reforms could extend those benefits to patients, doctors, and the health care system in the short and long term.

Improving essential care. Patients who need frequent touchpoints with their care team can more readily receive timely diagnoses and treatments, consistent care, and specialized help regardless of where they live or their ability to travel. It also eases the burden of coordinating schedules for lengthy, costly travel.

For Medicare, a more nationalized approach could also help scale health interventions nationwide rather than limiting them to state-by-state approvals, Hughes said.

“They’re also overwhelmed with a new diagnosis of cancer for themselves or for their child, and they shouldn’t have to fly across the country to get an opinion when they could spend 30 minutes to an hour getting a video consult. I think it’s quite unfair to put that burden on them.”

– Shannon MacDonald, senior medical director of the Southwest Florida Proton Center

Potential Medicare savings. There is some evidence to suggest that telehealth access is cost-saving to Medicare. Allowing patients to virtually visit with their trusted doctors when traveling is likely to help avoid unnecessary urgent care and emergency room visits.

MacDonald noted that patients who are unable to get care from their out-of-state specialist will often go to the emergency room, where they could get an incorrect diagnosis or medication.

“It will overburden emergency rooms that are already overburdened,” MacDonald said. “It just is so inefficient and so impractical in modern-day America, and it really makes no sense.”

More accurate research. Medical researchers often lose out-of-state participants to follow-up appointments during clinical trials, Hughes said. Expanding access to cross-state telehealth would make it easier for long-distance participants, particularly those who live in rural areas, to remain in trials. This helps ensure that research uses funding more efficiently and better represents different communities across the U.S.

Addressing key concerns of nationwide telehealth

The proposals put forward by Hughes and her colleagues also considers two key hesitations about expanding cross-state telehealth:

- Varying quality and standards of care from state to state

These proposed approaches don’t apply to all kinds of care. Rather, they focus on a narrow set of common-sense exceptions for specific high-impact populations, expanding access to essential care while maintaining the accountability and oversight of existing state-based licensure frameworks.

Under the proposal, providers would need to follow all relevant laws where the patient is located at the time of a visit, and a national group would oversee compliance with state laws and receive any complaints if they arose.

- Licensure revenue

By proposing expanded cross-state telehealth access for a narrow set of patients and services, the targeted approach would not drastically impact state medical licensing boards’ revenue from licenses. Additionally, any anticipated decreases in physician license fees could be offset by ongoing federal funding if there were federal oversight of telehealth expansion nationwide.

Hughes and colleagues plan to continue this work in partnership with advocacy colleagues, such as the American Telemedicine Association. Explore the policy approaches in more detail below.